About a Boy: A transgender teen at the tipping point

Jay dressed to disappear. He wore the same grey sweatshirt every day. (Family photo)

Jay woke in darkness, the summer and a girlhood behind him. A sharp pain stabbed through his stomach. In an hour, he would be a high school freshman.

Please, he thought, don't let anyone recognize me.

He dragged himself out of bed and lumbered through the double-wide trailer he shared with his mom and two sisters. His mother was at work, his siblings asleep. Only his dog, a 9-pound Chihuahua named Chico, marked Jay's passing from one life to the next.

Jay faced the bathroom mirror. He was 14. His dark brown hair spiked just the right way. His jaw was square, his eyebrows full and wild. But his body betrayed him. He was 5-foot-2 and curvy in all the wrong places.

He tugged one sports bra over his chest and then another. He pulled on a black T-shirt, hoping it would hide his curves. He eyed the silhouette, and his stomach rumbled with anxiety.

Not flat enough.

He had finished eighth grade with long hair and a different name. At his new school in southwest Washington, most of the 2,000 kids had never known the girl Jay supposed he used to be. As long as his contours didn't give his secret away, "Jay" was a clean slate, a boy who could be anyone.

He took one final look in the mirror. Puberty was pulling him in a direction he didn't want to go, and reversing it would take more than a haircut and an outfit. But how much more? He was a boyish work in progress, only beginning to figure out how to become himself. His mom and his doctors had little precedent for how to help.

He had taken great pains to start school as this boy with no past. His mom had met with the principal, and a counselor had created a plan. Jay could use the staff bathroom. Teachers would avoid his birth name, a long and Latina moniker that stung Jay every time he heard it.

Jay stepped outside and knew he should feel lucky. Whole generations had lived and died without any of the opportunities he would have. He was a teenager coming of age in an era Time magazine had declared the Transgender Tipping Point.

By his senior year, Jay's quiet life would ride a surge in civil rights.

Barack Obama would become the first president to say the word "transgender" in a State of the Union speech. Target would strip gender labels off its toy aisles. In Oregon, student-athletes would gain the right to decide whether to play on the girls' team or the boys'. Girls would wear tuxedos to prom.

That didn't make the path forward easy or safe. North Carolina would forfeit $3.7 billion to keep people like Jay out of the bathroom. An Oregon city councilman an hour from Jay's house would threaten an "ass-whooping" to transgender students who used "the opposite sex's facilities." Even Washington, the liberal state Jay called home, would consider a bill rolling back his right to choose the locker room that felt right. President Donald Trump would take over for Obama and ban transgender people from serving in the military.

But that morning, Jay was just a teenager, just a boy walking to school. He didn't want to be a trailblazer. He wanted to be normal.

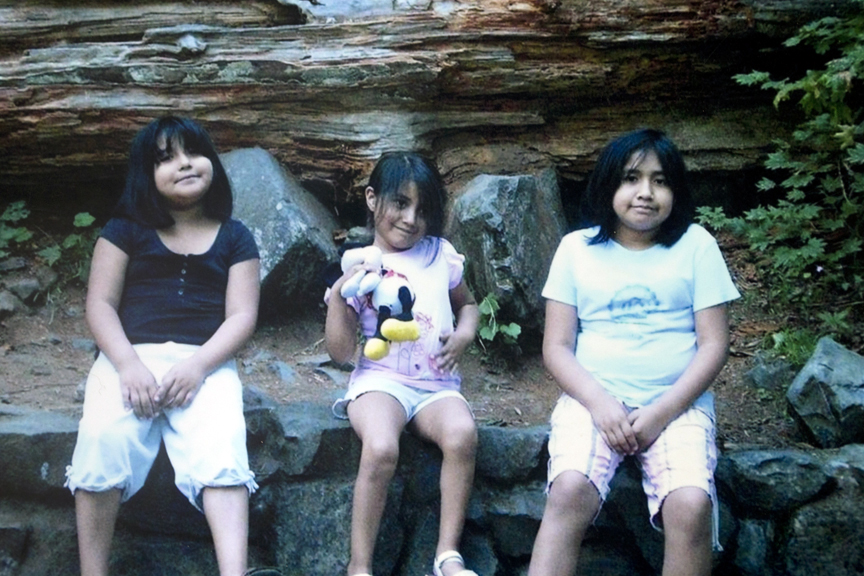

Jay (right) had been depressed since he was 4. In photos, he grimaced while his sisters Maria (left) and Angie (center) smiled. (Family photo)

"THAT'S NOT ME"

He was 12 when "girl" started to feel like the wrong word for him.

I'm a ghost without a body. A vampire. No mirrors for me.

His reflection found him anyway. There were mirrors in the hallway and next to the kitchen table. Turned off, the flat-screen TV was a black projection of the body he tried to hide. Even the coffee table, a glass-top smeared with after-school snacks, caught his form.

His face was round and so was his body. He turned away in disgust.

That's not me.

His family called him YaYa then. He dressed to disappear. He pulled his thick hair into a ponytail, the imperfect gathering too far left or right to be stylish. He wore an oversized gray sweatshirt every day and kept the hood up to hide his hair.

He tried to do what other girls did. He shaved his eyebrows and curled his hair. Both felt wrong. His stomach knotted every time someone called him "she."

In other parts of the country, people might have talked. Girls in guys sweatshirts were tomboys or worse. In Vancouver, Washington, a suburb just north of Portland, most people looked the other way. He had friends who wore makeup, but no one ever pressured him to try it.

Still, some days, he couldn't bring himself to walk the hallways. He skipped class at least once a week in seventh grade. He passed whole days in bed, the sheets pulled up to his neck. In the shadows of his bedroom, Jay could be almost nothing at all.

His mother took him to doctors, but there was no word for the way Jay felt. He struggled to explain that he felt sick because he didn't feel like himself.

I feel like I am walking on glass, he wanted to say. But the words came out, "My stomach hurts."

The doctor gave him omeprazole for heartburn and Zofran for nausea. Jay trawled the internet for a better diagnosis. Surfing on a years-old iPod, he landed on YouTube, where every video was a current that pulled him toward another. Eventually the river carried him to a four-minute video called "BOYS CAN HAVE A VAG." A 20-something woman with long hair and perfect eyebrows laid out her argument.

READ THE REST OF PART ONE ON OREGONLIVE